Chapter X

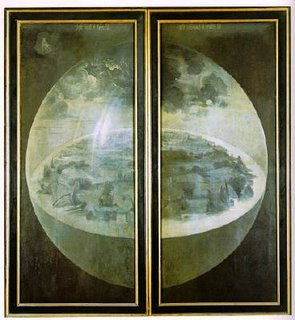

As any parent will tell you, the growing pains of an infant child are many and varied, both for the child itself and for those around it. Life becomes all the more difficult for the child if it does not have stability. So it was with the Bubble whose mother – the blessed Joanna – had died in childbirth, and whose surrogate parents – Reverend Dalrymple and his second lieutenant, Mr Seggar – had died as martyrs for the cause of the Bubble’s moral fortitude.

There had been, as we have seen, much confusion in the countryside. Rivers and streams ran uphill and burst their banks; animals previously unnoticed by the naked eye expanded colossally and took to the skies; and the former giants of the animal world – great mammals and carnivores and underwater predators – shrunk to the size of fleas. In the towns as well there had been considerable damage. But it was the relationships between people which were most significantly altered by the Bubble’s foundation. The leaders of the old world – politicians, landowners, squires and ministers – had been so shaken by this turbulence which they could do nothing about, that they tended to stay at home in the early days of the Bubble. But the common people of the world – “the Real People,” as they referred to themselves – had decided that it was best to act early in order to effect change. It was they who had been the powerless and the disenfranchised in the old world, and they were not prepared to submit to such paralysis again. Nevertheless, they were faced with a considerable dilemma. Most of the Real People had nourished an allegiance to God in the old world. Their doctrines differed considerably, and the God of one particular group would have been unrecognisable to another. But, nevertheless, a belief in God and a belief in humanity were the tenets which bound the groups together, however tenuously. By denouncing the presence of God, Reverend Dalrymple and Mr Seggar had taken away their reason for living. They had to somehow reclaim Him without reneging the ethics their founding fathers had set down.

A decision was made by Mr Tozer, who as Joanna’s friend had assumed some responsibility for her creation. He arranged a meeting for the leading lights in London to meet in the Palace of Westminster, which, in the confusion of the Bubble’s birth and growth, had been dumped temporarily on a beach on the south-west coast, and discuss the future of the Bubble. Somebody somewhere – a Radical most likely – had spread the word and invited everybody he knew, in the belief that a discussion about everyone’s future by a select few was a discussion not worth having. The same man had also arranged for some light entertainment to precede the discussion: a strongman friend called Timothy Service who amused the people by lobbing planks of wood through the Palace’s windows. This angered some people, who found the idea of wanton destruction blasphemous and distasteful; others found it hilarious or empowering or incendiary or, in a few cases, carnally arousing. In any case, it had the desired effect of reclaiming the Palace as a public building, and as such one that the people could do with as they pleased. One man was even spotted carefully extracting window-panes and door-frames and taking them home to repair his house with.

The group gathered in the House at half-past eleven o’clock and Mr Tozer, who had assumed the role of Speaker, led the House in saying prayers. Mr Tozer opened the discussion with some opening remarks.

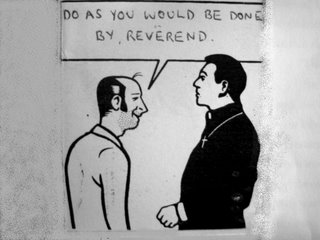

Mr Speaker (Mr. William Tozer): I must welcome the House to this important debate regarding the constitutional affairs of our new world. I would like first to set out some ground rules. The first is that is we are here under God’s ceiling because we are all equal in his eyes. In this respect, I would ask that all Members remain quiet while another is talking, and would also request that each Member listens with a careful ear to his Friend’s opinions. My second plea is for each Member to speak his mind in its totality without fear of restraint or rejoinder. An opportunity such as this does not occur every new moon or even every blue moon. We must make the most of it. Miss Harriet Clarke, please!

Miss. Harriet Clarke (layperson): I thank you, Mr Speaker, for your moving welcome, and I thank everybody here for coming. I would echo what you said, Mr Speaker, and simply add my own counsel for the good people in this place today. It is this: the Palace in which we sit or stand today is the place appointed by God for the purpose of bettering our society through honest government and the gentle rule of law.

Respectful applause from the Members of the House.

Miss. Clarke: Those who sat in this place before us to talk money and pass laws did not have our best interests at heart. They governed us scornfully, favouring the propertied and the monied. Most of us here are neither propertied nor monied. I myself am a mother of four; my husband is a phlebotomist. None of us are schooled; my husband earns a dreadful wage which we share amongst us the best that we can; the house we live in does not belong to us, and our landlord – a true scoundrel – might take it away from us as his fancy takes him. I, like most of you here, have never voted for anyone, nor made any contribution as to how I am permitted to live. That is why I am grateful to take advantage of this opportunity to talk to you all, and urge you to think about your family and friends and neighbours who are not able to be here today. It is them, as well as ourselves, we must have in our thoughts.

Cheers from the House. Shouts of “Liberty!” etc.

Mr. Speaker: Mr Max Baker.

Ironic cheers.

Mr. Max Baker (Independent and Reformist): Mr Speaker. Ladies and Gentlemen. I shall not, you will be relieved to hear, allow deliberations to be protracted through cause of my own speech.

More cheers and laughter.

Mr Baker: But, Mr Speaker, I would like to make a brief point about the nature of time, if I might be permitted.

Mr Speaker: If you must make your point about time, Mr Baker, please ensure you do not exhaust too much of it in doing so!

Great laughter from the House. Slapping of thighs, clutching of foreheads, general mirth etc.

Mr Baker: I take your point, Mr Speaker. There are several theories about the nature of time. Some of these are archaic – though, to some, still somewhat relevant – and some are relatively modern. One could quite logically make the claim that ideas about time should not be prejudiced by its passing, but such is the temper of ideas, the development of which must inextricably be linked to human development, that it is often assumed, and at times with good reason, that philosophical thought is bound to improve over time, including those thoughts about time. One of the most interesting ideas I have heard about time, which I became privy to purely by chance in an establishment located in one of the more respectable areas of a northern town, whose name I shall not disclose here, is that it follows a cyclical path. For the purposes of elucidation, I should like to introduce you to an imaginary traveller. Let us call him –

Voice from the rear of the house: Saint Christopher!

Mixed emotions from the House. Those of a decadent nature roar with laughter once again, while the more sensitive Members frown and pray for this wicked wit’s soul.

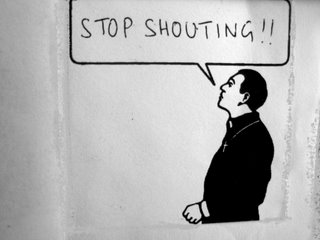

Mr. Speaker: Order. Let the gentleman speak.

Mr. Baker: Let us call him –

Uproar continues. A missile of paper is lobbed across the House..

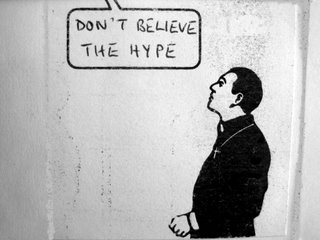

Mr Speaker: Order. Really, ladies and gentlemen. I must remind you of your surroundings. I have granted this urgent debate and I can stop it at will. If Members shout, that is what I will do, so they have a choice.

Uproar subsides.

Mr Speaker: Now, Mr. Baker. Continue, and please heed my warning and aspire to brevity.

Mr. Baker: I am merely seeking to explain the point, which I overheard in the northern town to which I made reference earlier, that time does not work in terms of a journey which our unnamed traveller might take. It does not have a starting point; it does not stop for rests or sustenance; and it does not have a terminus. It simply goes round and round and round: never quickening nor slowing down, never resting nor tiring: just continuing to pass. I am striving to explain this point, which some Members amongst us today might find contentious, intelligently so I am surprised that certain sections of the assembled find cause to get so aerated.

High-pitched “ooh”s of derision from the House.

Mr. Baker: But the implication is this: we are compelled to do what is right for us now. We are no nearer to the end of history than we were a year, ten years, a hundred or a thousand years ago. We should not be troubled by how the future will judge us. We must do what is right for the Bubble now!

Cheers from the House.

Mr. Speaker: Mr John Hood, please.

Mr. John Hood (Calvinist): Mr Speaker, I thank you for the wise words you used to open this debate and congratulate the previous speakers on their cogency. I myself find it ungodly that we are having a debate of this kind at all –

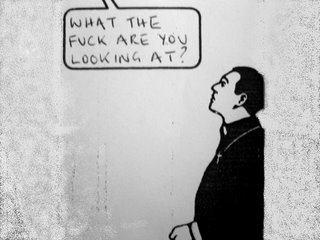

Roars of objection from the House.

Mr. Speaker: Order. You may not like what Mr Hood has to say but please remember my ground rules. The quicker he is allowed to make his point, the quicker we can return to sensible discourse. (to Mr Hood) I apologise, Mr Hood, but that is my view.

Mr. Hood: It is one you are entitled to hold. For my own part, I consider that you live in Satan’s kingdom, and thus any opinion you air in my direction is quite irrelevant. But if I am allowed to continue –

Mr. Speaker: I shall not stand in your way.

Mr. Hood: Much obliged. I myself find it ungodly that we are having a debate of this kind at all, and there are five reasons I would like to give for this assertion.

Mr. Speaker: (in disbelief) Five?

Mr. Hood: They are all quite short.

Mr. Speaker: Very well. Proceed.

Mr. Hood: The first, Mr Speaker, ladies and gentlemen, is related to your residence in Satan’s kingdom. If you have not subjected yourself to the transcendence of God – and your various delusions of creating a future of your own making clearly indicate you have not – then you must clearly be very evil people indeed. I do not say this in order to offend; in fact, I am very much enjoying the pleasure of your company this morning, and would like to invite those of you who are able to join my wife and I at church on Sunday. She is cooking a goose for lunch, which the more profligate among you may enjoy. Nevertheless, in failing to give every part of yourselves to God, you are all clearly very depraved indeed. My second point is that I too am depraved. I sin regularly and, were it up to me, I should have stoned myself to death many years ago. Thankfully it is not up to me – nothing is! – and such is the beneficence of God that I am forgiven for my sins and can therefore be here to talk to you today.

Voice from the back: More’s the pity!

Laughter from the House.

Mr. Speaker: Order. I sympathise with your objection sir, but trading insults will not enable this debate to progress.

Mock tutting from the House.

Mr. Speaker: Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. Mr Hood, please proceed.

Mr. Hood: My third point is that your eventual conclusion today is irrelevant, since God has predetermined the course which the world will take, and which of us is suitable for salvation.

Voice from the back: But surely that means he has pre-determined what conclusion we will reach today? And that means whatever is decided – even if we decide to determine our own destinies and say yah-boo to old dyed-in-the-wools like yourself – will have God’s backing.

Sensation in the House.

Mr. Speaker: They do say He works in mysterious ways. Anyway – who’s next? The Duchess of –

Mr. Hood: (interrupting) But I still have two outstanding points!

Mr, Speaker: I think we can surmise what they might be, Mr Hood, since your first three all more or less said the same thing.

Laughter in the House.

Mr. Hood: But –

Mr. Speaker: You might like to send any concerns you have regarding the democratic processes of this House in writing to the Serjeant-at-Arms.

Mr. Hood: Is there such a person?

Mr. Speaker: Certainly. You are talking to him now.

Hubbub in the House.

Mr. Speaker: Order gentlemen please. Thank you. Now – who have we next? Mr Feversham?

Mr. Feversham (Chiliast): Grace be unto you, and peace, from him which is, and which was, and which is to come; and from the seven Spirits which are before his throne; and from Jesus Christ, who is the faithful witness, and the first begotten of the dead, and the prince of the kings of the earth. Unto him that loved us, and washed us from our sins in his own blood, and hath made us kings and priests unto God and his Father; to him be glory and dominion for ever and ever. Amen.

House: (confused) Amen.

Mr. Feversham: (with high drama) I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea. And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself will be with them, and be their God. And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away. And he that sat upon the throne said, Behold, I make all things new. And he said unto me, Write: for these words are true and faithful.

Mr. Speaker: Yes, speaking of words, could Mr Feversham not also send these thoughts to the Serjeant-at-Arms in writing?

Mr. Feversham: And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and shewed me that great city, the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God, having the glory of God: and her light was like unto stone a most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal; and had a wall great and high, and had twelve gates, and at the gates twelve angels, and names written thereon, which are the names of the twelve tribes of the children of Israel.

Mr. Speaker: Order. Mr Feversham, I appreciate your respect for the authority of the scriptures, but there is really no need to out-God us all. We all of us here are good Christian folk –

Voice from the back: Speak for yourself!

Laughter in the House.

Mr. Speaker: Order. – but we did prayers earlier, so unless you wish to furnish us with information of a more relevant nature –

Mr. Feversham: Sir, perhaps I might point you towards the relevant bits in what I have just said?

Mr. Speaker: Proceed.

The House settles down again to listen to Mr. Feversham

Mr Feversham: In the passages with which I began my address, I referred to the lost tribes of the children of Israel. The events of the last week – the creation, I mean, of this thing which we are calling a Bubble – have seen the lost tribes of Israel dispersed far and wide –

Mr Speaker: – They have been spotted in Birmingham and Wapping, I believe.

Laughter in the House

Mr Speaker: Order. For the life of me I cannot see what is funny in that. Mr Feversham, continue.

Mr Feversham: I have read reports in the broadsheet newspapers and titbit weeklies of what has happened. Some, as we know, are claiming that a Bubble has consumed the world: beginning somewhere in the south-west of England, and spreading out in all directions until it had taken possession of the entire world and everything within it. This seems to me a barely plausible explanation, but it is not bad. Some are referring to something called a Big Bang and something called evolution: this, for my own part, I feel is deeply irreligious. Others are placing the whole affair at the feet of a late Devonshire woman, of whom God was apparently particularly enamoured. I do not know which of these explanations is correct, but I can report the following to you.

Air of expectation in the House.

Mr Feversham: On the morning when the full force of the Bubble (for I agree to call it that) was thrusting itself upon ourselves and our brothers and sisters, I spoke to God.

Mr. Speaker: (meekly) And what did He say, Sir?

Mr. Feversham: (ignoring Mr. Tozer) And as we spoke, I realised that the Bubble was in fact the work of God Himself.

Mr. Speaker: Did He confirm this?

Mr. Feversham: (irritated) One doesn’t ask God foolish questions, Mr. Tozer. Anyway, the point I am making is that it was only because I talked to God, and because of His infinite grace and mercy, that the world was not completely destroyed. I asked Him if he might spare us, so that we could build a new city where there is no more death or sorrow or crying or pain. All this was what the Book of Revelations prophesied; in our most desperate moments, all of us have wondered whether this day would ever come; and now, ladies and gentlemen, it has! I can see the new Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God, having the glory of God: and her light shall be like unto stone a most previous, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal; and it shall have a wall great and high with twelve gates, and at the gates there shall be twelve angels, with names written thereon. Can you see the new Jerusalem? Can you? Will you?

House descends into triumphant and passionate applause, cheers, women fainting etc.

It was at this point in the discussion that, to most of the assembled party, the Bubble suddenly made sense. Ever since Reverend Dalrymple had rolled down the hill from Ottery St. Mary’s churchyard, all eyes had been on the Bubble. It was all anybody had spoken about since Christmas. Those outside the Bubble wondered what it could be and why it had come; and those inside it wondered what it could mean. There were as many theories as there were people, but now Mr Feversham had offered up an explanation that everyone could believe in. It was not simply an act of Nature or – pshaw! – evolution. The Bubble actually meant the end of civilisation and the coming of Christ. Like a politician, Mr Feversham had asserted his millenarian claims with just enough logic to make them plausible, and his zeal was such that it divided the House into two discrete groups. One was led by Mr Feversham and its manifesto was to work towards the new Jerusalem of which he had received such stunning vision. The other (something of an omnium gatherum) was made up of people who, for various reasons, distrusted Mr Feversham and his lofty rhetoric. And in between these two groups were the majority: wavering, unsure which camp to pitch in, and feeling every bit as powerless as ever.

Anyhow, Mr Tozer concluded the Debate with some fine platitudes, including a passing tribute to the Duchess of Marlborough’s hat, and the group then dispersed.

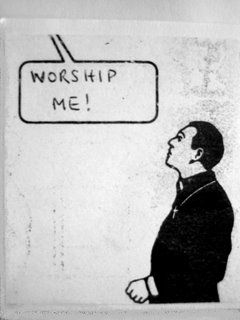

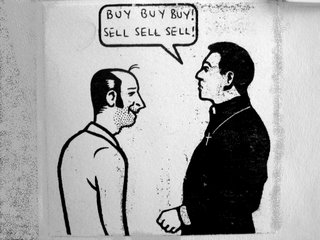

The following weeks saw further debate among men and women of learning on both sides, so that extreme points of view gradually became moderated and sensible policies began to be applied. Normal people carried on regardless. It seemed curious to some that the rulers of the Bubble were so keen to appear to act on their behalf, while at the same time working as if they were in an elite cabal, a more civilised species as it were. But such was the desire of these rulers (from Reverend Dalrymple and Mr Seggar through to Mr Feversham and the future Prime Minister, the Duke of Marlborough) to assert their authority that they persisted in forever moving the goalposts, so that

WORSHIP ONLY GOD

had become

THERE IS NO GOD

which became

EVERYONE IS GOD

which became

EVERYONE IS NOTHING

which became

SOME PEOPLE ARE SOMETHING.

Some people were something, and the majority were nothing: faceless, nameless nobodies, useful when it came to elections, but with no other specific function in society. The people of the Bubble instantly accepted this. They had always been nobodies, and they could see no reason why the birth of a new world would change that.

END OF BOOK ONE