Chapters VIII and IX

VIII

On the eighth midday since the Bubble’s birth, and the first since it had been substantially populated, Reverend Dalrymple and Mr Seggar held their first Committee meeting. It was held in a spherical space, approximately ten feet in diameter, dead in the centre of the Bubble where Reverend Dalrymple had set up his home.

During the confusion of the Bubble’s first rapid expansion, the Reverend had taken a large oak table which had spilled out of some duke or other’s residence. It had been the duke’s, but it was now in the spherical space, and was therefore Reverend Dalrymple’s. He had decided he would write committee reports and design grand strategies and urban plans for the Bubble at this table. It barely fit in his ten foot by ten foot spherical space, but for now it served as ground control.

Although Mr Seggar had been the second person to enter the Bubble (by about five days), Reverend Dalrymple agreed that they would be joint Chairs of the Committee. “Two heads,” he said astutely, “are better than one.” There were no other constituents present, and Membership was not one of the agenda items. These were:

1. Apologies

2. Terms of Reference

3. Governance

4. Any other business

Mr Seggar volunteered to take minutes.

“Very well,” said Reverend Dalrymple, “shall we begin?” Mr Seggar held his pen a centimetre above the page ready to note salient points.

“Any apologies?”

“I haven’t received any.”

“Me either.” There was a pause.

“You should write Item one, colon, Apologies, then underline it. Then underneath write None.”

“I see.” Mr Seggar did this.

“Have you written the title of the meeting, and the date, and who is present?”

“No.”

“You should do that as well.” Mr Seggar began to write something down, then scribbled it out.

“What is the title of the meeting?”

“The title of the meeting? Ah.” Reverend Dalrymple scratched his eyebrow and sniffed. “A New World Management Board,” he said authoritatively. Mr Seggar wrote this down, along with the date and his and Reverend Dalrymple’s names, at the top of the page.

“The next item is Terms of Reference. Do we have any?”

“I haven’t brought any,” said Mr Seggar.

“Me either. I shall draft the Terms of Reference for the next meeting.”

“We are having another meeting?” asked Mr Seggar, surprised.

“Many more meetings, Mr Seggar, many more. Now. I shall draft the Terms of Reference for the next meeting. That is called an action point. You should write Reverend Dalrymple – or RD – to draft Terms of Reference for the next meeting, then underline it.” Mr Seggar wrote this, not knowing what Terms of Reference meant.

“Now. Governance. This is a very big topic, Mr Seggar. A very big topic indeed. So big that it may take several meetings to thrash it out properly.”

“What does it mean?”

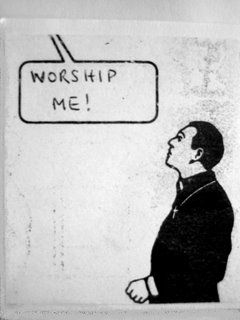

“Well, Mr Seggar, you and I were the first people to enter this place. I was the first and you were the second. Before you became the second, do you remember what you asked me? Down in Ottery village square?” Before Mr Seggar could reply, Reverend Dalrymple answered his own question. “You asked me if I was God.”

“Yes,” agreed Mr Seggar.

“Do you know the answer to your question?”

“I’m not sure,” said Mr Seggar.

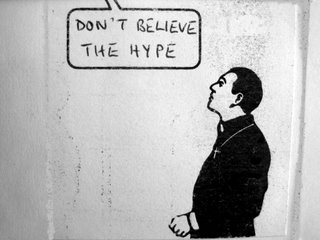

“Well, Mr Seggar. Let me tell you something about human life. You needn’t minute this, but you may wish to take some brief notes for your own reference. Now, Mr Seggar, the first thing to say about human life is that it is made up of two distinct groups. Not men and women; not employer and employee; not clever and stupid or rich and poor. Creators and survivors. Those are the two groups, Mr Seggar: creators and survivors.” Mr Seggar wrote down Creators and Survivors. “Some people cling onto their mortal coil for dear life, just because they feel thankful to be on the coil at all, to have something – anything! – on which to cling. But there are other people who want nothing more than to let go of the coil and to find out what is inside of it, or outside of it; what it looks like from above, or below; whether you can break it, smash it to pieces, use it as a spring; whether it has a beginning or an end, or whether it is a moebius strip which never begins or ends and which has no middle and therefore no real measurements at all. Do you understand what I am saying, Mr Seggar?”

“A mortal coil,” murmured Mr Seggar doubtfully.

“Creators and survivors.” Reverend Dalrymple got up from the table and began to pace around his spherical space, looking out onto the Bubble. “Survivors survive through instinct. Something – a voice, perhaps, but one which they don’t hear – tells them that they should carry on whatever they were doing yesterday and last week and last month. They have no free will to do any different. Only creators have this. Creators let go of the mortal coil and some fall into black holes and stay there for a split second which equals eternity. But others find new coils and new creations. Some are made from coloured matter daubed over a coarse cloth – you will find these in a gallery. Some are made from air vibrations controlled by blowing or hitting or picking or scraping – you will hear these in a concert-hall or on a record. Some are made from dyed fluids stamped or engraved onto reprocessed wood in more formations than any sensible man could count – these are on your bookshelf, Mr Seggar, if indeed you have one.”

“They are books,” said Mr Seggar eagerly.

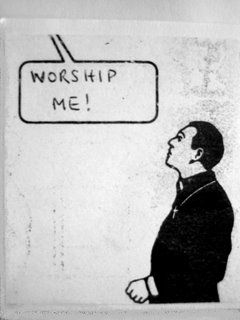

“Indeed they are. But another of these creations is the planet Earth. God, using his own free will, created the planet Earth, and thereby established his own existence. A painter does the same, as does a musician, or an author. All these are Gods. I created the Bubble, and so, to answer your question, I am God. Having established this, I call on you to help me decide precisely, or as precisely as is possible, what it is that I have created. To do this you will also have to be a creator. Have you created anything before, Mr Seggar?”

“No.”

“Do you have a wife?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have any children?

“Yes.” A look of excitement arched over the Reverend’s face.

“Did you intend to?”

“No.” With great sinking shoulders Reverend Dalrymple sighed and looked at the floor.

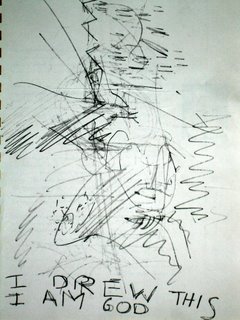

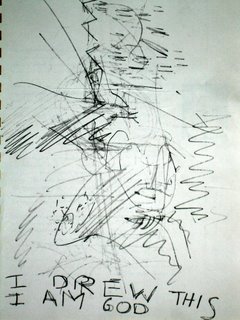

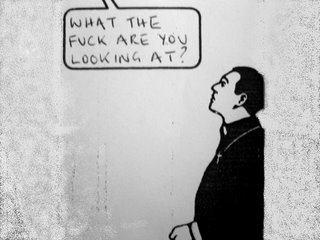

“You are, I’m afraid, a survivor, Mr Seggar. This is something we must change. We will work together to make you a creator like me!” Mr Seggar and Reverend Dalrymple looked at each other. They looked at each other for some time, trying to synchronise their psyches. After a while Mr Seggar began grinning. His eyes grew wider and took on a glisten and a shimmer. He bared his teeth at Reverend Dalrymple in a horrible and beautiful grin. His nostrils flared and a prickly sweat covered his face. Reverend Dalrymple looked at him and looked at him until he started not to look like Mr Seggar at all. Mr Seggar started to write something. Reverend Dalrymple furrowed his brow and looked at Mr Seggar as if he were a medical experiment. Mr Seggar wrote and wrote, then scrawled and scrawled, with the energy of a wild animal. His hand was not making any logical movement. It was like the hand of an untamed concert conductor as it flailed and flopped and carved deep black scores and smudges onto the paper. Then he stopped, and with his own free will wrote six clear words under the mess of the picture on the page:

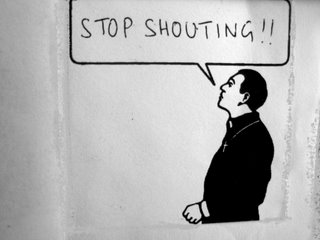

Reverend Dalrymple took the piece of paper, ripped it up, and threw the pieces outside of the spherical space at the centre of the Bubble. They flew in every direction and dissolved into thin air. He said to Mr Seggar:

“I destroyed your picture. Now we are both God.”

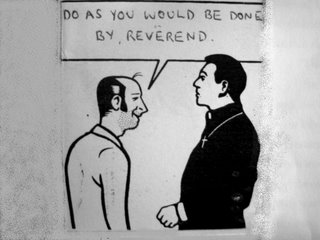

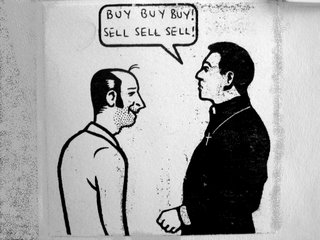

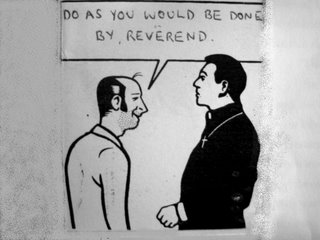

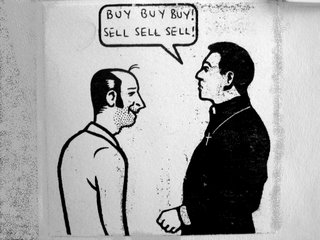

And thus they set about governing the Bubble. Firstly, they agreed that the planet Earth, the world they had left behind, was bad. It was ruled by the wrong people and these people killed the other people over whom they ruled. The people who were the rulers were the creators, but with their free will they created death. The people who were the ruled were the survivors, but their instincts told them to obey the ruler and die, and some didn’t know the difference between living and death. This happened over and over and over so that history was no longer history and probably never had been. It was just an endless series of repetitions. Reverend Dalrymple had created a new world for the first time since God. The Bubble would take over the world, God was dead, and Reverend Dalrymple, with Mr Seggar, was now God. Having established the world’s rottenness, they decided that the Bubble must be entirely different. It must share none of the old world’s traits. Rules must change; feelings must change; thoughts and the way in which they are expressed must change; morals must change; time and space themselves must change. Ultimately, Reverend Dalrymple idealised, people would not think in terms of rules, feelings, thoughts, expression, morals, time and space, or anything else. But he knew this would take time. He must start small. So he and Mr Seggar, in their first New World Management Board, discussed the accepted morals and immorals from the old world.

They then decreed that all morals and immorals must be reversed so that what was once moral was now immoral and must be outlawed, and what was once immoral was now moral and should be rewarded. At the end of the meeting, the two men killed each other. This is how the meeting ended.

IX

It was now early evening and time for William to be getting back home to Kate and the boys. He had not worked especially hard today if truth be known; but then again he had not earned a penny. He had been given a sitting down job to do – counting 100 bolts into little cardboard boxes – so he had the whole day for his head to go wherever it chose. So it dreamed about being crushed in a riot; it thought about the church where he’d said his prayers yesterday and how he might suggest to Kate that they could escape to the bell-tower one night with some beer on credit from the pub, and some cigarettes, and he could try and woo her like he had done when they were kids.

And that got him thinking about his own kids, and whether one day there might be something – maybe a revolution, because people spoke about revolutions all the time – which might mean that his boys could have a good story to tell their grandchildren. William had, ever since he was a boy, lived in a world where whatever he did or did not do, whether he bore children or killed his own mother, his actions would have no impact at all on the world. None at all. He had been born thirty-four years ago, had received a rudimentary education for a few years and had been mostly left to pasture; then he had become a labourer on a farm in Kent; then a gardener; then he met Kate and married; then they had two kids; then he had been made redundant and found another job in a factory which he knew exactly how to blow up and take with it most of Camden and Highgate and Finsbury Park. There was a story in there somewhere but William did not know how he was going to tell it to his grandchildren. They would not care that in all his time alive he had worked, read a bit, had sex, eaten meals, got drunk, said his prayers, gone to his parents’ funerals and tended their graves without having any effect on the world whatsoever. This did not make him angry but it did make him wonder why he was alive and whether anyone else thought like this. It was this that made him want to go “AAAAAAAAAA” and get a boot stamped in his face.

But it was no good. Nothing would happen to make his boys grow into real people. William would keep his head down, try not to get too drunk on Sundays, and wait for the recession – or whatever it was that they called poor people dying – to end. The Blackstocks would be OK even if the Tanners and the Pirellis would not. His boys would get better jobs than William had managed and get more money. They would get married and have children of their own to worry after. But they would never mean anything to anybody except themselves. If they became sufficiently affluent that they had leisure time to enjoy, the things they would fill their evenings and weekends with would be as boring as filling little cardboard boxes with bolts. William could feel himself breathing. He could still feel his heart beating from all that beer last night. But really he knew he was dead, and that Kate and the boys were dead too, and he only wished he could tell them.

William signed out from the factory and began to walk home. He felt a pinging and a tingling in his ears. He walked past a school which had just been demolished, then past the police station, then past a slum. He looked back and saw trees and a field full of rape and something which looked like running water. He wanted to pick apples from the trees and lie in the rape and roll his trousers up to his ankles and take a dip in the river. But something pushed him onwards and made him realise he could not go back. He had heard the managers and the mechanics say something about a force (that was what they called it) which was coming from the west and which would change the world. All the factory was in a great tiz about it. William couldn’t have cared less as he put his 97th bolt in the box. But when he couldn’t climb a tree that was barely twenty yards away, or smell the rapeseed oil of a field he could see glowing beside a copse, or feel a cool trickle of water running over his hand – it was then that he realised the Bubble did exist and that he was the only person in the world who wasn’t inside it.

CHAPTER X OUT ON 19 AUGUST 2006

On the eighth midday since the Bubble’s birth, and the first since it had been substantially populated, Reverend Dalrymple and Mr Seggar held their first Committee meeting. It was held in a spherical space, approximately ten feet in diameter, dead in the centre of the Bubble where Reverend Dalrymple had set up his home.

During the confusion of the Bubble’s first rapid expansion, the Reverend had taken a large oak table which had spilled out of some duke or other’s residence. It had been the duke’s, but it was now in the spherical space, and was therefore Reverend Dalrymple’s. He had decided he would write committee reports and design grand strategies and urban plans for the Bubble at this table. It barely fit in his ten foot by ten foot spherical space, but for now it served as ground control.

Although Mr Seggar had been the second person to enter the Bubble (by about five days), Reverend Dalrymple agreed that they would be joint Chairs of the Committee. “Two heads,” he said astutely, “are better than one.” There were no other constituents present, and Membership was not one of the agenda items. These were:

1. Apologies

2. Terms of Reference

3. Governance

4. Any other business

Mr Seggar volunteered to take minutes.

“Very well,” said Reverend Dalrymple, “shall we begin?” Mr Seggar held his pen a centimetre above the page ready to note salient points.

“Any apologies?”

“I haven’t received any.”

“Me either.” There was a pause.

“You should write Item one, colon, Apologies, then underline it. Then underneath write None.”

“I see.” Mr Seggar did this.

“Have you written the title of the meeting, and the date, and who is present?”

“No.”

“You should do that as well.” Mr Seggar began to write something down, then scribbled it out.

“What is the title of the meeting?”

“The title of the meeting? Ah.” Reverend Dalrymple scratched his eyebrow and sniffed. “A New World Management Board,” he said authoritatively. Mr Seggar wrote this down, along with the date and his and Reverend Dalrymple’s names, at the top of the page.

“The next item is Terms of Reference. Do we have any?”

“I haven’t brought any,” said Mr Seggar.

“Me either. I shall draft the Terms of Reference for the next meeting.”

“We are having another meeting?” asked Mr Seggar, surprised.

“Many more meetings, Mr Seggar, many more. Now. I shall draft the Terms of Reference for the next meeting. That is called an action point. You should write Reverend Dalrymple – or RD – to draft Terms of Reference for the next meeting, then underline it.” Mr Seggar wrote this, not knowing what Terms of Reference meant.

“Now. Governance. This is a very big topic, Mr Seggar. A very big topic indeed. So big that it may take several meetings to thrash it out properly.”

“What does it mean?”

“Well, Mr Seggar, you and I were the first people to enter this place. I was the first and you were the second. Before you became the second, do you remember what you asked me? Down in Ottery village square?” Before Mr Seggar could reply, Reverend Dalrymple answered his own question. “You asked me if I was God.”

“Yes,” agreed Mr Seggar.

“Do you know the answer to your question?”

“I’m not sure,” said Mr Seggar.

“Well, Mr Seggar. Let me tell you something about human life. You needn’t minute this, but you may wish to take some brief notes for your own reference. Now, Mr Seggar, the first thing to say about human life is that it is made up of two distinct groups. Not men and women; not employer and employee; not clever and stupid or rich and poor. Creators and survivors. Those are the two groups, Mr Seggar: creators and survivors.” Mr Seggar wrote down Creators and Survivors. “Some people cling onto their mortal coil for dear life, just because they feel thankful to be on the coil at all, to have something – anything! – on which to cling. But there are other people who want nothing more than to let go of the coil and to find out what is inside of it, or outside of it; what it looks like from above, or below; whether you can break it, smash it to pieces, use it as a spring; whether it has a beginning or an end, or whether it is a moebius strip which never begins or ends and which has no middle and therefore no real measurements at all. Do you understand what I am saying, Mr Seggar?”

“A mortal coil,” murmured Mr Seggar doubtfully.

“Creators and survivors.” Reverend Dalrymple got up from the table and began to pace around his spherical space, looking out onto the Bubble. “Survivors survive through instinct. Something – a voice, perhaps, but one which they don’t hear – tells them that they should carry on whatever they were doing yesterday and last week and last month. They have no free will to do any different. Only creators have this. Creators let go of the mortal coil and some fall into black holes and stay there for a split second which equals eternity. But others find new coils and new creations. Some are made from coloured matter daubed over a coarse cloth – you will find these in a gallery. Some are made from air vibrations controlled by blowing or hitting or picking or scraping – you will hear these in a concert-hall or on a record. Some are made from dyed fluids stamped or engraved onto reprocessed wood in more formations than any sensible man could count – these are on your bookshelf, Mr Seggar, if indeed you have one.”

“They are books,” said Mr Seggar eagerly.

“Indeed they are. But another of these creations is the planet Earth. God, using his own free will, created the planet Earth, and thereby established his own existence. A painter does the same, as does a musician, or an author. All these are Gods. I created the Bubble, and so, to answer your question, I am God. Having established this, I call on you to help me decide precisely, or as precisely as is possible, what it is that I have created. To do this you will also have to be a creator. Have you created anything before, Mr Seggar?”

“No.”

“Do you have a wife?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have any children?

“Yes.” A look of excitement arched over the Reverend’s face.

“Did you intend to?”

“No.” With great sinking shoulders Reverend Dalrymple sighed and looked at the floor.

“You are, I’m afraid, a survivor, Mr Seggar. This is something we must change. We will work together to make you a creator like me!” Mr Seggar and Reverend Dalrymple looked at each other. They looked at each other for some time, trying to synchronise their psyches. After a while Mr Seggar began grinning. His eyes grew wider and took on a glisten and a shimmer. He bared his teeth at Reverend Dalrymple in a horrible and beautiful grin. His nostrils flared and a prickly sweat covered his face. Reverend Dalrymple looked at him and looked at him until he started not to look like Mr Seggar at all. Mr Seggar started to write something. Reverend Dalrymple furrowed his brow and looked at Mr Seggar as if he were a medical experiment. Mr Seggar wrote and wrote, then scrawled and scrawled, with the energy of a wild animal. His hand was not making any logical movement. It was like the hand of an untamed concert conductor as it flailed and flopped and carved deep black scores and smudges onto the paper. Then he stopped, and with his own free will wrote six clear words under the mess of the picture on the page:

Reverend Dalrymple took the piece of paper, ripped it up, and threw the pieces outside of the spherical space at the centre of the Bubble. They flew in every direction and dissolved into thin air. He said to Mr Seggar:

“I destroyed your picture. Now we are both God.”

And thus they set about governing the Bubble. Firstly, they agreed that the planet Earth, the world they had left behind, was bad. It was ruled by the wrong people and these people killed the other people over whom they ruled. The people who were the rulers were the creators, but with their free will they created death. The people who were the ruled were the survivors, but their instincts told them to obey the ruler and die, and some didn’t know the difference between living and death. This happened over and over and over so that history was no longer history and probably never had been. It was just an endless series of repetitions. Reverend Dalrymple had created a new world for the first time since God. The Bubble would take over the world, God was dead, and Reverend Dalrymple, with Mr Seggar, was now God. Having established the world’s rottenness, they decided that the Bubble must be entirely different. It must share none of the old world’s traits. Rules must change; feelings must change; thoughts and the way in which they are expressed must change; morals must change; time and space themselves must change. Ultimately, Reverend Dalrymple idealised, people would not think in terms of rules, feelings, thoughts, expression, morals, time and space, or anything else. But he knew this would take time. He must start small. So he and Mr Seggar, in their first New World Management Board, discussed the accepted morals and immorals from the old world.

They then decreed that all morals and immorals must be reversed so that what was once moral was now immoral and must be outlawed, and what was once immoral was now moral and should be rewarded. At the end of the meeting, the two men killed each other. This is how the meeting ended.

IX

It was now early evening and time for William to be getting back home to Kate and the boys. He had not worked especially hard today if truth be known; but then again he had not earned a penny. He had been given a sitting down job to do – counting 100 bolts into little cardboard boxes – so he had the whole day for his head to go wherever it chose. So it dreamed about being crushed in a riot; it thought about the church where he’d said his prayers yesterday and how he might suggest to Kate that they could escape to the bell-tower one night with some beer on credit from the pub, and some cigarettes, and he could try and woo her like he had done when they were kids.

And that got him thinking about his own kids, and whether one day there might be something – maybe a revolution, because people spoke about revolutions all the time – which might mean that his boys could have a good story to tell their grandchildren. William had, ever since he was a boy, lived in a world where whatever he did or did not do, whether he bore children or killed his own mother, his actions would have no impact at all on the world. None at all. He had been born thirty-four years ago, had received a rudimentary education for a few years and had been mostly left to pasture; then he had become a labourer on a farm in Kent; then a gardener; then he met Kate and married; then they had two kids; then he had been made redundant and found another job in a factory which he knew exactly how to blow up and take with it most of Camden and Highgate and Finsbury Park. There was a story in there somewhere but William did not know how he was going to tell it to his grandchildren. They would not care that in all his time alive he had worked, read a bit, had sex, eaten meals, got drunk, said his prayers, gone to his parents’ funerals and tended their graves without having any effect on the world whatsoever. This did not make him angry but it did make him wonder why he was alive and whether anyone else thought like this. It was this that made him want to go “AAAAAAAAAA” and get a boot stamped in his face.

But it was no good. Nothing would happen to make his boys grow into real people. William would keep his head down, try not to get too drunk on Sundays, and wait for the recession – or whatever it was that they called poor people dying – to end. The Blackstocks would be OK even if the Tanners and the Pirellis would not. His boys would get better jobs than William had managed and get more money. They would get married and have children of their own to worry after. But they would never mean anything to anybody except themselves. If they became sufficiently affluent that they had leisure time to enjoy, the things they would fill their evenings and weekends with would be as boring as filling little cardboard boxes with bolts. William could feel himself breathing. He could still feel his heart beating from all that beer last night. But really he knew he was dead, and that Kate and the boys were dead too, and he only wished he could tell them.

William signed out from the factory and began to walk home. He felt a pinging and a tingling in his ears. He walked past a school which had just been demolished, then past the police station, then past a slum. He looked back and saw trees and a field full of rape and something which looked like running water. He wanted to pick apples from the trees and lie in the rape and roll his trousers up to his ankles and take a dip in the river. But something pushed him onwards and made him realise he could not go back. He had heard the managers and the mechanics say something about a force (that was what they called it) which was coming from the west and which would change the world. All the factory was in a great tiz about it. William couldn’t have cared less as he put his 97th bolt in the box. But when he couldn’t climb a tree that was barely twenty yards away, or smell the rapeseed oil of a field he could see glowing beside a copse, or feel a cool trickle of water running over his hand – it was then that he realised the Bubble did exist and that he was the only person in the world who wasn’t inside it.

CHAPTER X OUT ON 19 AUGUST 2006

3 Comments:

Thanks Alexandra - I always take "interesting" as more of a compliment than "good," so glad to hear it's intriguing you.

Sorry for the delay in replying to your comment btw - my email didn't show that anyone had commented recently. So thank you again - you have lifted my veil of despondency!

excuuuse me - the last post was 12th August - it's September tomorrow!!

Jesus - I bet Dickens didn't have to put up with grief like this.

OK, OK, I have been slack. It's all that energy I have expended making compilations for a certain somebody...

More chapters to follow this evening...

Post a Comment

<< Home