Chapter IV

IV

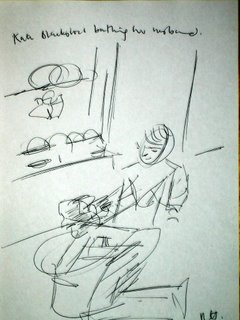

The Blackstocks were too poor to live properly, but they did have enough money to live in a condition almost befitting human beings. This made them unloved and resented in their neighbourhood. A look around Kate Blackstock’s kitchen showed an iron pail, oblong and three feet and eighteen inches at its longest lines of longitude and latitude, standing in the corner beside a large antique bureau which had become mulchy through lack of polish. The pail was filled once or twice a week with tepid water (in fact, it was not filled: the water level was only three or four inches off the base). Kate, dressed in the dirty white blouse she wore everyday with sleeves rolled up, an equally dull skirt and an apron patterned with endless rows of diamonds, would kneel on the carpet, which had been kneeled on so much you couldn’t see the pattern. With a small pinched smile and blank eyes she would scrub the grime from her dirty husband’s torso and face while he knelt on all fours. The pail wasn’t big enough for a proper bath, but since they had no soap its size was irrelevant.

The smell in the house was awful. It was the smell of two adults and two children living filthily. Stacked up on the bureau were William’s mother’s china plates and milk-jugs. The bureau was his mother’s too. Everything in the house either had a grandeur rooted in the past, or else had no grandeur at all.

But the point was that the Blackstocks did own things. William’s pathetic wages and the boys’ game efforts at scrumping bought just enough food to keep skin and bones and muscles in their right places. And Kate had never miscarried and her two children were still alive and mostly healthy. Kate was the only mother in the street who could make these claims, and this was another reason why the street disliked her and saw her as puffed-up and above them. Jessica Tanner from no. 41 had lost two of hers within six months of each other – her sense of relief each time was palpable:

“I thank God for it! I am relieved from the burden of keeping them and they are relieved from the troubles of mortal life.” Jessica had worked as a seamstress and her wages were not enough to feed herself for breakfast for three days. With her husband who knows where, she had flown to the streets to make her living. She had nothing else, except her three other children, mother and elderly aunt. All six of them squeezed into a basement underneath the street which had originally been built to conceal rubbish. Kate had once had occasion to go into the Tanner’s house. It immediately struck her as appalling: joyless, pitiless and inhuman. Walking down the steps from the pavement, you entered the main room, which split its function between kitchen, sitting room and bedroom, depending on the time of day or the family’s needs. As soon as you were in this main room, your eyes were drawn to its various phenomena. Firstly, two wooden chairs which, like the other chairs in the house, were eaten up with woodworm and whose seats were made up of collapsed sacking. These two chairs stood at the back of the room, just in front of a stack of shelves. On the left hand chair sat Jessica Tanner’s mother. She was in her late forties but looked at least seventy. She was a large woman whose size, when compared to the waifs around her, made her look quite obscene. Kate had heard a story about old Mrs Tanner being visited by a doctor for some minor ailment and telling her friends afterwards, “I’ve got a good mind to report that Doctor Springer. He reckoned I should lose some weight. You know what he called me? He said, ‘Mrs Tanner, you’re a beast.’” Kate had laughed when she had heard the story. She couldn’t remember who had told her it. Perhaps it was the doctor. Nobody else in the street would tell her anything like that. Anyway, old Mrs Tanner would sit on the chair on the left and Baby would sit on the chair on the right. Baby was a doll which had been Jessica’s as a child. It was a biggish doll with a cherubic face and rosy-red cheeks. It still bore the marks of the seven-year-old Jess, who would draw eyeliner on Baby’s eyes with a graphite pencil. The doll had since lost all its hair, which drew attention to its weird, brick-red complexion. Its head was too big for its body; its tiny arms hung from its torso like flabby pink sausages and its legs had been sawn off above the knee. Its expression was one of censorious scrutiny. All the family secretly hated it, and it terrified the children, but Baby always sat there, judging them and never revealing its thoughts.

Elsewhere in the room there was a series of shelves, mostly dipping in the middles, which supported a jumble of chipped crockery, warped ironware and other bric-a-brac. Centre right was the dinner table, covered by last week’s newspapers, dragged out of the rubbish-bins on Sunday when they should have been at church. Centre left was the bed where the children slept. In the back right hand corner was a pile of dust and plaster where Jack Stubbs from upstairs had fallen out of bed and gone through the ceiling. All this sounds bad enough to the person who sees these things as the reader of a book, but the Tanners had to live in these disgraceful and disgusting conditions and only they really knew the darkness and misery of living there.

Kate did not see the other rooms: the bedroom in which Jessica’s baby, her mother and her grubby and silent great-aunt slept, and in which Jessica and her latest punter would sometimes spend a night. All generations of the Tanner household were party to Jessica’s dishonour. The scullery was equally hateful: crumbling walls, yellow with age and oozing damp; a stink of human excrement from the blocked drain where a toilet had once stood; the musty air where one could feel bugs of cholera and typhoid and tuberculosis penetrating the pans and plates and cups from which the Tanners ate and drank.

Kate had felt enormously relieved after she had seen the Tanner’s house because she knew she lived so much more healthily and respectably than them. But she also knew that, however much their vacant faces suggested otherwise, the Tanners were human beings: in nature, if not in existence. Their house should have been condemned, and Kate did indeed condemn it. But this did the Tanners no good at all. They continued their lives for the good of nobody, least of all themselves.

CHAPTERS V AND VI OUT ON 25 JULY

The Blackstocks were too poor to live properly, but they did have enough money to live in a condition almost befitting human beings. This made them unloved and resented in their neighbourhood. A look around Kate Blackstock’s kitchen showed an iron pail, oblong and three feet and eighteen inches at its longest lines of longitude and latitude, standing in the corner beside a large antique bureau which had become mulchy through lack of polish. The pail was filled once or twice a week with tepid water (in fact, it was not filled: the water level was only three or four inches off the base). Kate, dressed in the dirty white blouse she wore everyday with sleeves rolled up, an equally dull skirt and an apron patterned with endless rows of diamonds, would kneel on the carpet, which had been kneeled on so much you couldn’t see the pattern. With a small pinched smile and blank eyes she would scrub the grime from her dirty husband’s torso and face while he knelt on all fours. The pail wasn’t big enough for a proper bath, but since they had no soap its size was irrelevant.

The smell in the house was awful. It was the smell of two adults and two children living filthily. Stacked up on the bureau were William’s mother’s china plates and milk-jugs. The bureau was his mother’s too. Everything in the house either had a grandeur rooted in the past, or else had no grandeur at all.

But the point was that the Blackstocks did own things. William’s pathetic wages and the boys’ game efforts at scrumping bought just enough food to keep skin and bones and muscles in their right places. And Kate had never miscarried and her two children were still alive and mostly healthy. Kate was the only mother in the street who could make these claims, and this was another reason why the street disliked her and saw her as puffed-up and above them. Jessica Tanner from no. 41 had lost two of hers within six months of each other – her sense of relief each time was palpable:

“I thank God for it! I am relieved from the burden of keeping them and they are relieved from the troubles of mortal life.” Jessica had worked as a seamstress and her wages were not enough to feed herself for breakfast for three days. With her husband who knows where, she had flown to the streets to make her living. She had nothing else, except her three other children, mother and elderly aunt. All six of them squeezed into a basement underneath the street which had originally been built to conceal rubbish. Kate had once had occasion to go into the Tanner’s house. It immediately struck her as appalling: joyless, pitiless and inhuman. Walking down the steps from the pavement, you entered the main room, which split its function between kitchen, sitting room and bedroom, depending on the time of day or the family’s needs. As soon as you were in this main room, your eyes were drawn to its various phenomena. Firstly, two wooden chairs which, like the other chairs in the house, were eaten up with woodworm and whose seats were made up of collapsed sacking. These two chairs stood at the back of the room, just in front of a stack of shelves. On the left hand chair sat Jessica Tanner’s mother. She was in her late forties but looked at least seventy. She was a large woman whose size, when compared to the waifs around her, made her look quite obscene. Kate had heard a story about old Mrs Tanner being visited by a doctor for some minor ailment and telling her friends afterwards, “I’ve got a good mind to report that Doctor Springer. He reckoned I should lose some weight. You know what he called me? He said, ‘Mrs Tanner, you’re a beast.’” Kate had laughed when she had heard the story. She couldn’t remember who had told her it. Perhaps it was the doctor. Nobody else in the street would tell her anything like that. Anyway, old Mrs Tanner would sit on the chair on the left and Baby would sit on the chair on the right. Baby was a doll which had been Jessica’s as a child. It was a biggish doll with a cherubic face and rosy-red cheeks. It still bore the marks of the seven-year-old Jess, who would draw eyeliner on Baby’s eyes with a graphite pencil. The doll had since lost all its hair, which drew attention to its weird, brick-red complexion. Its head was too big for its body; its tiny arms hung from its torso like flabby pink sausages and its legs had been sawn off above the knee. Its expression was one of censorious scrutiny. All the family secretly hated it, and it terrified the children, but Baby always sat there, judging them and never revealing its thoughts.

Elsewhere in the room there was a series of shelves, mostly dipping in the middles, which supported a jumble of chipped crockery, warped ironware and other bric-a-brac. Centre right was the dinner table, covered by last week’s newspapers, dragged out of the rubbish-bins on Sunday when they should have been at church. Centre left was the bed where the children slept. In the back right hand corner was a pile of dust and plaster where Jack Stubbs from upstairs had fallen out of bed and gone through the ceiling. All this sounds bad enough to the person who sees these things as the reader of a book, but the Tanners had to live in these disgraceful and disgusting conditions and only they really knew the darkness and misery of living there.

Kate did not see the other rooms: the bedroom in which Jessica’s baby, her mother and her grubby and silent great-aunt slept, and in which Jessica and her latest punter would sometimes spend a night. All generations of the Tanner household were party to Jessica’s dishonour. The scullery was equally hateful: crumbling walls, yellow with age and oozing damp; a stink of human excrement from the blocked drain where a toilet had once stood; the musty air where one could feel bugs of cholera and typhoid and tuberculosis penetrating the pans and plates and cups from which the Tanners ate and drank.

Kate had felt enormously relieved after she had seen the Tanner’s house because she knew she lived so much more healthily and respectably than them. But she also knew that, however much their vacant faces suggested otherwise, the Tanners were human beings: in nature, if not in existence. Their house should have been condemned, and Kate did indeed condemn it. But this did the Tanners no good at all. They continued their lives for the good of nobody, least of all themselves.

CHAPTERS V AND VI OUT ON 25 JULY

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home